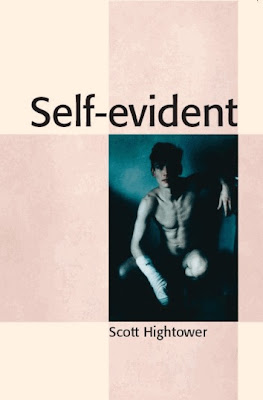

Always turning in clean work, Scott Hightower is someone who simultaneously is so present in the poetry scene and yet oddly almost underneath everyone's radar. Hopefully, his new book "Self-evident" will change that. It should. It's always been unfortunate that several gay poets of the same generation have often been eclipsed by their peer, the ubiquitous Mark Doty. I think that both Hightower and Doty (who is the older by a year) often share a similar temperament --a formidable strength sometimes-- and only sometimes-- accompanied by a piercing aggressiveness. Although Doty could reasonably be said to have a finer ear, I think that it's his choice to write personal narratives that has ultimately won him much more acclaim. Which is upsetting. Hightower's consistent personae poems can be as deftly crafted and as personal, maybe even more so.

One of my favorite poems, "Le Soldat Avec Les Besoins Infantiles," is largely an acute dramatic monologue in the voice of the female fairy addressed in Keats's "La Belle Dame Sans Merci." It could almost be read as a not-too subtle critique of Hightower's choice of the dramatic monologue as a genre. At the same time, Hightower doesn't self-deprecate to the point of a pure unnecessary dismissal. This sort of balanced self-reflexivity embedded in the structure of the poem makes it even smarter. Here's an excerpt:

...Afterwards, I knew

he would resort to grumbling

from some perverse shadow

of his own masochistic imagination,

that there would be a dramatic

monologue about being abandoned.

Would that he grasped that each

of us does well but to serve up

to the other the most ordinary joy!

The whole undulating world

is complete and florid,

is a single rhapsodic

motion. And, as you

and I will know--his

own gorgeous, archaic

whiny self-indulgence

included--everywhere, there

are sweet songs worth singing....

Like Richard Howard, a good number of Hightower's poems are historical in nature. His range is more than comprehensive. You have no idea who he's going to choose as the next subject for a poem. In this books, he includes filmmaker Sergei Parajanov, photographer F. Holland Day, Nobel prize-winning scientist Severo Ochoa, Casanova, and Benjamin Franklin. And that just scratches the surface. Ekphrastic poems also help fill the collection.

Some of my favorite poems include "Madrid, Please, Take Me; Be Mine" ("You are my Castilian/My Euskera, my Bable,/ My Pig Latin.); "There are Lecagies Beyond Land" (...I came to your granaries/ and lanes a bride, with only the dowry of poetry/ my sophistication green."); "Identity Redux" ("The wingless moon floats/beyond the encapsulating/spotlight, and each one/in the theatre must find/each's own way home."

You can feel the intellectual rigor in Hightower's interplay with high culture and history. This initially made me standoffish-- which may be an issue of class. Having parents who never went to college, I've perhaps always prematurely rejected poems that seem to be pushing a certain sort of academic elitism. This is often what I see as an overdetermined desire upon the part of gay poets to prove one's own work as legitimate through incorporating a lot of history and high-cultural allusions. Why do we need to be so well-rehearsed about the literary canon? Let's choose our own metaphors.

But, of course, this isn't a fair critique--there's a multiple number of ways political resistance and poetic novelty can be created. Hightower reminds us of that. And one of the things that's particularly clear about Hightower's books is that while he engages with such high-culture topics, he critiques this privilege --that's something that sets him apart. In his smartly titled "Lately, Opening the Refrigerator" he glosses a few of the people who've died from AIDS, and then jump-cuts to sitting in the Presidential box of the Prague opera house. He offers an appraisal ("The opera-which has never before/really quite worked for me...") and then ends describing the mise-en-scene:

...opens and closes in a garret,

two despairing choruses:

a group of grieving women,

a line of men lending

support to one another,

these broken things

of this world, this shelter.

The brilliant use of the word "shelter" and his placement of it on the final line is a small example of why Hightower is such an expert poet. In his own poems, he takes refuge in personae and history; at the same time, openly reveling in what personal truths may come from that. And offers those truths for-- at least for a moment-- what other, lesser poets may see as merely autobiographical "broken things."

You can receive more information about Scott Hightower's Self-evident at Barrow Street.

In a way, Aaron Smith's second full-length book collection, Appetite, is essentially a repackaging of his very fun, wonderful chapbook Men in Groups. This choice to make Appetite an extension of the chapbook rather than create something entirely new yields a limitation or two. A few of his additions feel dated: "The Problem with Straight People (What We Say Behind Your Back)," for instance, deals with gay rage, detailing the almost comic transcriptions of his friend's thoughts: "Brandon on the phone: We should start straight bashing. Find an asshole straight guy and beat him with a bad,/ fuck him in the ass." The centerpiece of the book consists of a prosaic litany of his favorite parts of movies. It lasts eight pages; he sometimes relies on the easy joke: "I love the part in Watchmen where Patrick Wilson is naked. I love the part in Hard Candy where Patrick Wilson is naked. I love the part in Passengers where Patrick Wilson is naked." The most memorable ones contain, to his credit, the most gutsy, depraved humor: "My friend Matt admitted he jerked off to the rape scene in The Accused: 'I knew she wasn't really being raped, and that one guy had a nice ass.'" The flat deadpan here works great. There are no apologies; Smith is good at being thoughtless and mean. It's his self-conscious that can from time to time deflate his own comic set-ups. A few of best poems here do come from the chapbook: "Diesel Clothing Ad (Naked Man with Messenger Bag)), "Fat Ass," and "Hurtful." With this book-length collection, you have to hunt around for them a little bit, rather than in the chapbook, they would pop up almost immediately. There's nothing anorexic about a chapbook; it can be a beautiful thing in and of itself.

In a way, Aaron Smith's second full-length book collection, Appetite, is essentially a repackaging of his very fun, wonderful chapbook Men in Groups. This choice to make Appetite an extension of the chapbook rather than create something entirely new yields a limitation or two. A few of his additions feel dated: "The Problem with Straight People (What We Say Behind Your Back)," for instance, deals with gay rage, detailing the almost comic transcriptions of his friend's thoughts: "Brandon on the phone: We should start straight bashing. Find an asshole straight guy and beat him with a bad,/ fuck him in the ass." The centerpiece of the book consists of a prosaic litany of his favorite parts of movies. It lasts eight pages; he sometimes relies on the easy joke: "I love the part in Watchmen where Patrick Wilson is naked. I love the part in Hard Candy where Patrick Wilson is naked. I love the part in Passengers where Patrick Wilson is naked." The most memorable ones contain, to his credit, the most gutsy, depraved humor: "My friend Matt admitted he jerked off to the rape scene in The Accused: 'I knew she wasn't really being raped, and that one guy had a nice ass.'" The flat deadpan here works great. There are no apologies; Smith is good at being thoughtless and mean. It's his self-conscious that can from time to time deflate his own comic set-ups. A few of best poems here do come from the chapbook: "Diesel Clothing Ad (Naked Man with Messenger Bag)), "Fat Ass," and "Hurtful." With this book-length collection, you have to hunt around for them a little bit, rather than in the chapbook, they would pop up almost immediately. There's nothing anorexic about a chapbook; it can be a beautiful thing in and of itself.